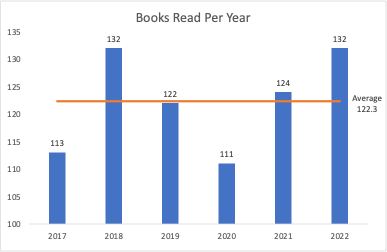

Over the last six years, I have read over 730 books. That works out to between two and three books per week!

Through this journey, I have discovered several insights about the learning process itself. If you want to improve your own ability to learn, these lessons will help you accelerate your personal development.

Readers benefit from the best time leverage

There are dozens of ways to learn, from workshops to YouTube videos to networking. All of these methods have a place. What distinguishes books as a learning medium is that the time leverage ratio is tilted dramatically in favor of the learner.

For any product, you can calculate a ratio for the amount of time the creator put into the work, compared to the time needed for the consumer to consume the work. In general, a higher ratio is better for the consumer. A single unit of the consumer’s time “gets more” of the creator, which is a decent proxy for quality.

Book readers capture the best time leverage of anything short of a Hollywood production. Writing a book takes a lot of time for the author, and the author spends more time working with an editor to improve the book for the intended audience. As a result, readers receive a product that is a refined form of the author’s expertise. The publishing process literally distills the author’s insights into a more potent form.

Compare the time leverage ratio of books to other common forms of learning materials. The vast majority of workshops are not polished to the same level as published books. Truly exceptional presenters may have invested the same amount of time, but they rarely have “edited” the workshop with as much attention to detail as a book receives.

Podcasts and YouTube videos are far easier to produce than books; just compare the number of aspiring creators who have launched a podcast to the number who have published a book! As a learner, the lower cost to entry means there is more content available. But, that content is unlikely to be as worked over as a book.

Again, there is a place for each medium in your learning approach. But, books are likely to give you the best bang for your learning time bucks.

One good book flattens the learning curve

Most people learn a new domain because they need it to solve a problem at work. The typical “process” is that they encounter a challenge, look for resources to overcome the challenge, and repeat when they face the next obstacle.

This process encourages a reactive learning style. The person learns what they need at the moment, but they are effectively wearing blinders to issues that they haven’t encountered yet. As a result, their learning is myopic. They miss opportunities early on the learning curve because, e.g., they don’t know the right followups to ask when they get advice from an expert, or they don’t realize that there are specific terms of art that would give them better resources when they are searching.

Reading a good book on a topic can flatten the initial learning curve. The reader can quickly learn the basic jargon, tools, and processes for a discipline. They can rapidly develop the conceptual framework to analyze their work, anticipate problems, and proactively seek support. They can normalize specific setbacks and understand typical strategies to overcome those setbacks. When they do tap into other resources, such as expert practitioners, training workshops, or recorded demonstrations, they will be able to watch for specific details and ask better questions, making those resources more valuable for them.

The best part is: there are literally dozens of entry points to any particular learning curve. You don’t need to pick the perfect book on, e.g., change management; you just need one that is reliable. It’s easy to find curated lists of book recommendations on specific topics. Pick a book that shows up on several of those lists, and you are off to a strong start.

Four books can equal two years of experience

To be clear: there’s no substitute for experience. But, one year of experience accompanied by four great books on a topic can easily be worth 2-3 years of experience alone.

This “equation” came out of the realization that a handful of great books on a topic could quickly move someone into an intermediate level of proficiency. What surprised me was how attainable the transition point was. A single book was not enough—but it also didn’t require dozens of books. The reward-to-effort ratio for those first few books is dramatic.

In practical terms, let’s say that you have read your first book and flattened the initial learning curve. You are now a competent beginner. You can continue to gain experience as a beginner, and over the next couple of years become conversant in the typical problems and solutions of your domain. Or, you can read another two or three books to really round out your understanding of the domain, and attain that same level of fluency by the end of your first year.

Let’s be conservative and say that you can only read one book per month. In the first month, you can teach yourself the absolute fundamentals and give yourself a foundation for further learning. In the following months, you can work through another major approach to the topic, dive into detail in a key skill that is challenging for you, and think through a sample project along with an author.

By the end of the fourth month, you’ve parlayed four books into a solid understanding of the field, a critical skill builder, and a case study that you have learned from vicariously. That’s more than a lot of people get out of two to three years of unstructured job experience!

Reading for learning is a skill

The benefits of reading to accelerate learning are clear. But it is important to realize that reading alone doesn’t cause learning. Reading for learning is a skill: it can be done better or worse, and your ability to learn from what you read can be improved.

Most reading occurs as a form of entertainment. Even popular business books, which are targeted at working professionals who want to benefit themselves and their organizations, are formatted as entertainment. The books follow the standard storytelling structure, introducing a protagonist who struggles with the problem du jour (or should I say du chapitre?) before finding the solution and heroically overcoming the obstacle. The solution is told with just enough detail to engage the reader, and key details are glossed over if they don’t fit the narrative pacing.

There’s nothing wrong with reading as entertainment. Personally, I think it’s one of the best forms of entertainment available! But, the techniques we use to read for entertainment are not always productive when attempting to read for learning.

If you are reading but don’t feel like you are learning much from the experience, it’s worth evaluating your reading techniques. You don’t have to read dry textbooks in order to learn from your time investment, but you do need to be intentional about your activity. Good reading for learning techniques include making predictions about what will happen, clarifying distinctions between what you have read and what your background knowledge tells you, searching for concrete details to support broader claims or principles, and reflecting on how these lessons could be applied to the work you are doing.